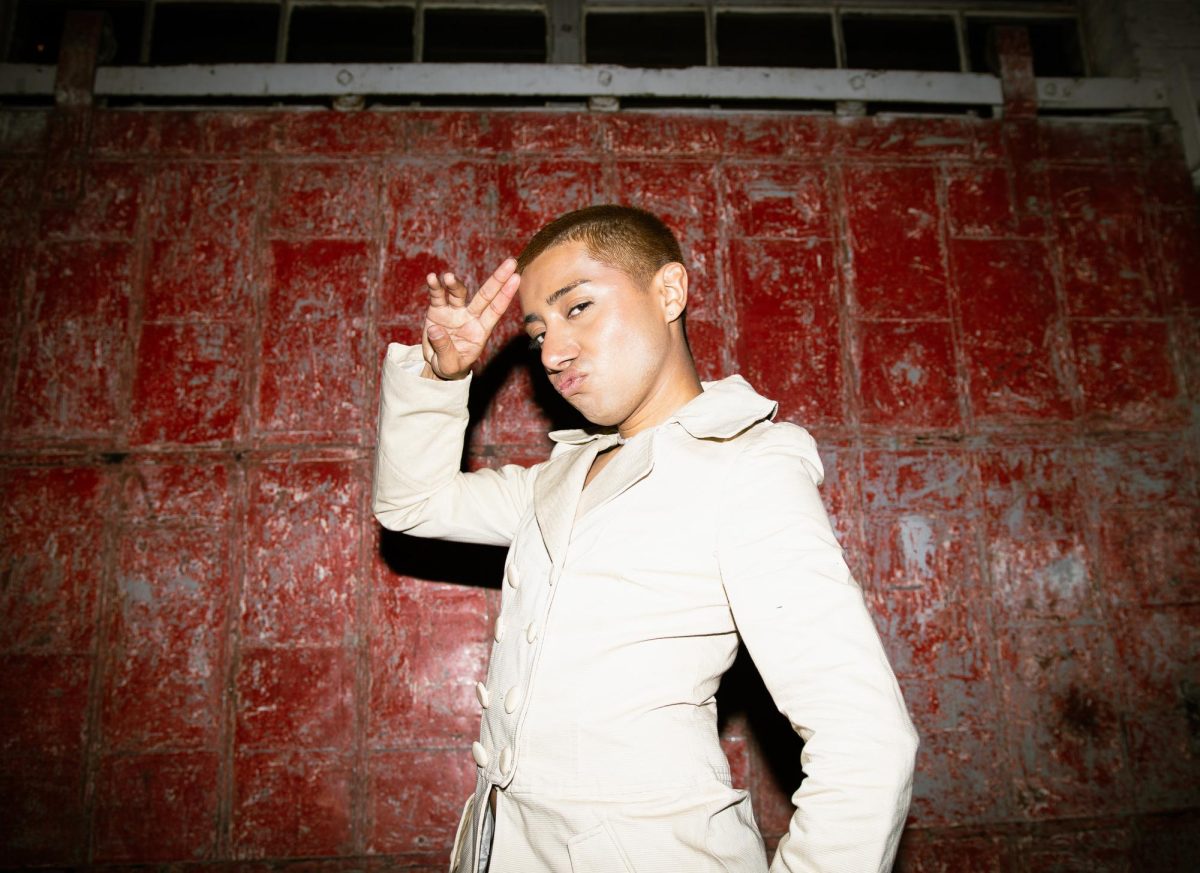

Gris Muñoz is the writer that just gave us the new Chicanx gospel and pillar of Chicanx literary canon: Coatlicue Girl. The book that just goes over 100 pages is a collection of stories and poetry weaved together by illustrations by artists Los Dos, took over a decade to come together.

Luis Alberto Urrea, the prominent Chicanx author of books such as “The Devil’s Highway”, wrote the foreword for the “rock and roll curandera.”

“Like so many great Chicana scriptures laid down in our past, this is an announcement of arrival and a crie de coeur,” wrote Urrea.

Muñoz’s Coatlicue Girl explores self-discovery and represents as much for the author. The stories and poems written in her early 20’s and onward explore ancestral and personal pain: they delve into self-discovery and nirvana in the Chicanx and queer identity.

In an interview conducted through email, Gris Muñoz talks about her origins as a writer, the process of how this book came to be and much more.

1. Can you talk a little bit about yourself; give us a brief overview about how you started writing and where you’re from.

I was born and raised in the lower valley of El Paso, my parents were both born in El Valle de Juarez, in a small town called Guadalupe Bravo. I mention Guadalupe several times in the collection. Like so many of us, I have been writing a long time. I wrote as a child but became disconnected from it after I graduated from high school. I actually began performing slam poetry when I was twenty-four, which feels like a lifetime ago. I went back to The University of Texas at El Pasoin my early to mid-thirties to study Literature and Creative Writing. I’ve been a working artist for sixteen years now. I’m a poet by trade but have received more accolades for my short stories. I am currently commissioned to write the biography of LA artist, Fabian Debora.

I’ve also been a student/practitioner of Curanderismo for about sixteen years. It’s something I inherited on both sides of my ancestry. It’s not something I put on my bio, but it’s another aspect of my truth. I have sat with indigenous elders and learned and also completed my commitment of four years of Danza Xochimeztli, or Moon Dance, in Mexico. I see women, children and families here in my community, mostly focusing on limpias and platica. My specialty: untwisting hearts. You can see it in Coatlicue Girl if you really want to.

2. ‘Coatlicue Girl’ plays with genre, comprising of poetry, fiction, and illustrations. How were you able to organize so many different forms all within one book?

Overall, I think the multi-genre pieces in Coatlicue Girl seem so cohesive because I’m always writing about the same shit! This border, these languages, this chasm, it’s who I am. But my work has always been multidisciplinary. I love performance, costume. I’ve written and performed a play and a one-woman show; I’ve even dabbled in stand-up comedy. There’s an aspect of constantly challenging myself. I just knew that I wanted to create something new, something modern. Having been inspired by all of the traditional Chican@ lit, I wanted my book to be in conversation with that genre. Ultimately though, I was just writing about my life.

3. This book was a project that you said took about ten years to start and finish. What does that mean? Did you always have this intention of a hybrid book titled ‘Coatlicue Girl’? Or did it kind of reveal itself along the way to you?

It took thirteen! I am extremely meticulous.

I wanted to show that I could create what I considered a ‘serious’ debut, you know, a single-genre collection. I struggled with the idea of putting out a hybrid collection for years. I think I felt like I had a lot to prove; being low-income, being queer, being a single mom, being from the lower valley, not having a traditional college experience…basically, being under estimated my whole life. I had this baggage of consistently feeling like I wasn’t taken seriously as a writer because I had a spoken-word background. People assumed I hadn’t read my fair share of ‘literature’, especially because my work was so heavily Chicanx. At one time I separated it into three manuscripts: English poems, Spanish poems and short stories. But it was impossible not to notice that they all seemed to fit together. Even then, it was a struggle.

It’s difficult to admit that I used to kind of look down on hybrid collections. I would assume that the author just didn’t have enough material or something and after years of struggle I had to admit how colonized my view of literature actually was.

I asked myself, ‘Who is my audience?’ That helped a lot. My response was, ‘Well, Chicanx like me.’ I saw how a hybrid collection actually described me exactly: A bisexual, bilingual fronteriza. And it’s defiant. I didn’t want to translate the Spanish pieces into English because I wanted to denote that nuance, how the language chosen for each piece was a deliberate choice, how there are things better said in each dialect.

4. The illustrations of course, done by (famous El Paso artists) Los Dos, are a prominent element in the book. You had mentioned that you paid out of pocket to have them do those illustrations. Can you talk a bit about why you went to them and what that process was like?

I believe that every piece of art has a destiny, just like we do. It has its own trajectory about coming into ‘being’. It sounds pretentious but stay with me. So, my background with Los Dos is very organic. We were neighbors in Sunset Heights. I had company one night and didn’t have a wine opener. I thought of them and ran outside and saw their light was still on. That was really my first contact. We became friends. They were already getting famous then, but they’re much bigger now. By that time, I knew I was going to title my debut book, Coatlicue Girl. I knew that much. One of my favorite aspects of Los Dos’ work is its playfulness, even while navigating extremely difficult truths. Their style is intensely original and pure border. I picked what I felt were the best pieces of my three manuscripts and assembled them into one to give them as a guide. As a collaborator, I did not want to infringe any of my ideas onto their impression of my work. I wasn’t going to be like, ‘Illustrate this particular piece.’ I gave them complete artistic liberty to create the images that the pieces inspired in them. I think that’s an important aspect of collaboration and art in general. People can be too controlling of their work, which in turn makes it heavy. I trusted them, right? They were geniuses. And I wanted to be surprised, too. That makes it fun.

I was also a single-mom and full-time student. I didn’t have a lot of money, so they agreed to let me pay them in payments. I felt bad that I had so little to offer them but think its proof of how much they care about helping artists in the community. The seed was planted and I forgot about it for a while. They called me three years later. The illustrations were done. The pieces they chose to illustrate confirmed it was meant to be a hybrid collection.

5. This book is very biographical for you. All except the final story are based on true events in your life. What has it been like having these pieces out in the world now?

It’s pretty surreal. In the opening scene in Beer Run, I am sitting on the hood of my car smoking a joint in front of my parent’s house in the lower valley. I describe the house. It’s meant as a loose foil to the opening in House on Mango Street, to its protagonist, “Esperanza.” I’m letting the reader know that this girl ain’t no Esperanza, and I’m no Sandra Cisneros. I didn’t come out of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. I’m the girl no one encouraged to take her SAT’s, who was told because she was the youngest and only daughter of four, could never leave town for college. There’s a cutting honesty there. “I guess I disappointed you, too,” I say aloud to McGruff the Crime Dog, who believed in me. It’s a funny scene, but she’s big sad. She’s a disappointment. The whole family is worried about her and there’s a deep self-deprecation there, a sadness she can’t name.

That was me. Unhappy because I was far away from my destiny. I wrote Beer Run when I was twenty-six, but I was probably about twenty-two when it happened. It’s kind of odd publishing stories you wrote at twenty-six when you’re thirty-nine, that actually happened at twenty-two. Because I’m not that girl anymore, or am I?

It’s a cartography of my life, as it was happening. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a book like that. I write about the first woman I loved, that only happened after I became a single mom. I write about poverty and motherhood; I write about power and how it positions itself in this city. I wrote about my lovers, male and female; the ones that left an impression, good or bad.

I wasn’t sure if it was going to feel dated or not. I had to take that risk, because it took its own time.

Honestly, finally putting it out, and it’s touching hearts? It’s healed me.

6. So on Instagram, when I shared the photos we took, you mentioned that the poem “Dorada” was one of your favorites but hasn’t gotten that many shoutouts. What does that poem mean to you?

It’s a weird little poem, and it’s loaded.

Polvoréame dorada

con tus manos de ateísta

y con tu boca moteada de tinta

declara que no soy sagrada

y

lánzame fuera de tu ventana,

figurilla rara.

No me molesta ser chiquita.

Mas prefiero ser la

basurilla animada por el viento

que

estatua bronceada sentada en la plaza,

monumento olvidado a caricias y poesías

pasadas.

There’s that recurring aspect of being an outcast, on the fringes. In it, I’m actually talking to an ex-partner of mine. It kind of goes along with another piece called “Spirits.” He was atheist, and in it I’m implying that because of that, he was unable to see my sacredness. That’s definitely not how I see atheism or atheists, but this relationship was actually emotionally abusive and I wrote it with that lens, of not being seen for my beauty, which has a lot to do with my spirituality. So I’m saying, just throw me away, then, if I’m not sacred at all. But then I make a jab, I say, I don’t mind being small. When you’re small you can dance with the wind and I’d rather be that than some heavy bronze statue that sits there, enshrined but with forgotten relevance. So here again I’m talking about the Chicana Greats, how they are revered but trapped, heavy. I’m basically talking shit. I’m telling the dude, ‘You don’t see my worth?! Ha! The whole genre doesn’t see my worth but look at who they revere.’ I guess it’s about permanence, but also truth. I know I’m Dorada, even if I’m not enshrined, sitting in a plaza.

Maybe the poem goes really deep, like, maybe I know too much about some writers.

I cover that again in “Speck.” In it, she frees the Virgen statue, who is trapped, exhausted from standing on the altar. The Virgen is essentially the genre and how bored/boring it is, cemented in its theory.

7. I’ve mentioned to you multiple times how much I loved the book and I could go poem by poem and talking about their meaning. But I guess the one I have to ask about as well is the titular poem, “Coatlicue Girl”. Why was this poem that one that would carry the title of the book? What does the name or title Coatlicue Girl mean for you?

I pressed my copper mouth

against the thin of her eyelid,

delicada

blink green-veined like

folding cricket wings

In the echoing valley

you lay beside me,

breasts-

stones

I had forgotten, Coatlicue Girl

there lives the hum of mantis,

the macaw in you

Five-hundred years later

I remember

This one is also layered. Throughout the book, I write about indigeneity and more so, the loss of indigeneity for colonized people. There’s a lot of wondering going on, about inheritance, about traditions, about ancestral memory. In the poem, Coatlicue Girl, I associate discovering my queerness with the act of decolonization. I’m saying that queerness was my true nature, just like my indigeneity.

I first wrote the poem about a woman I had an intense crush on, that’s where that desire aspect comes from. But its meaning morphed throughout the years. I became Coatlicue Girl. It’s about the inquisition and ancestral memory.

8. So another really strange thing is how you really shipping out copies just as the pandemic started. Has the book itself or any of the texts within changed meaning for you during the quarantine? What has it been like going through this process during this time?

Honestly, it’s taken a lot of pressure off of me. I was extremely anxious about putting it out after 13 years of work and although I was devastated when I had to cancel my book tour, I now admit there was a sense of internal relief. The book’s success has surprised me, because after so many years of work, there were definitely times I almost gave up on this project. Maybe I’m just overly intense, but I felt the stakes were high. I’m in El Paso, not in LA. I’m either going to put something out that people buy and stick in their shelves forever or maybe, it’ll call them with its own mojo. Maybe they’re going to pass it along to someone. I was very nervous, knowing that. It was either going to fly or it wasn’t. And that’s all art, you know? There’s an aspect of letting go. You can’t keep your thumb on the paper plane. You have to build it well so it can fly on its own. I’m now watching it fly. It’s not published by one of the big presses, but it’s moving well. So many times, you hear a lot of buzz about a book but that buzz never touches you. There’s no friend that says, “You have to read this book!” And what good is that? A long time ago, a professor told me, “Don’t write to a particular genre. Your audience will find you.” At the time I thought it was bullshit. “Who’s going to find me?” I thought.

But here we are.

9. Is there any specific goal or effect you want readers to take away from the book?

I can’t control what readers get from it (because I don’t want to) but I do hope they see my heart and hopefully, a bit of themselves. I also want to remind you and anyone reading that you and our practice can exist outside of academia.

You can follow Gris Munoz on Instagram and twitter @grismunozgris or at her website www.grismunoz.com.

By: Antonio Villaseñor-Baca