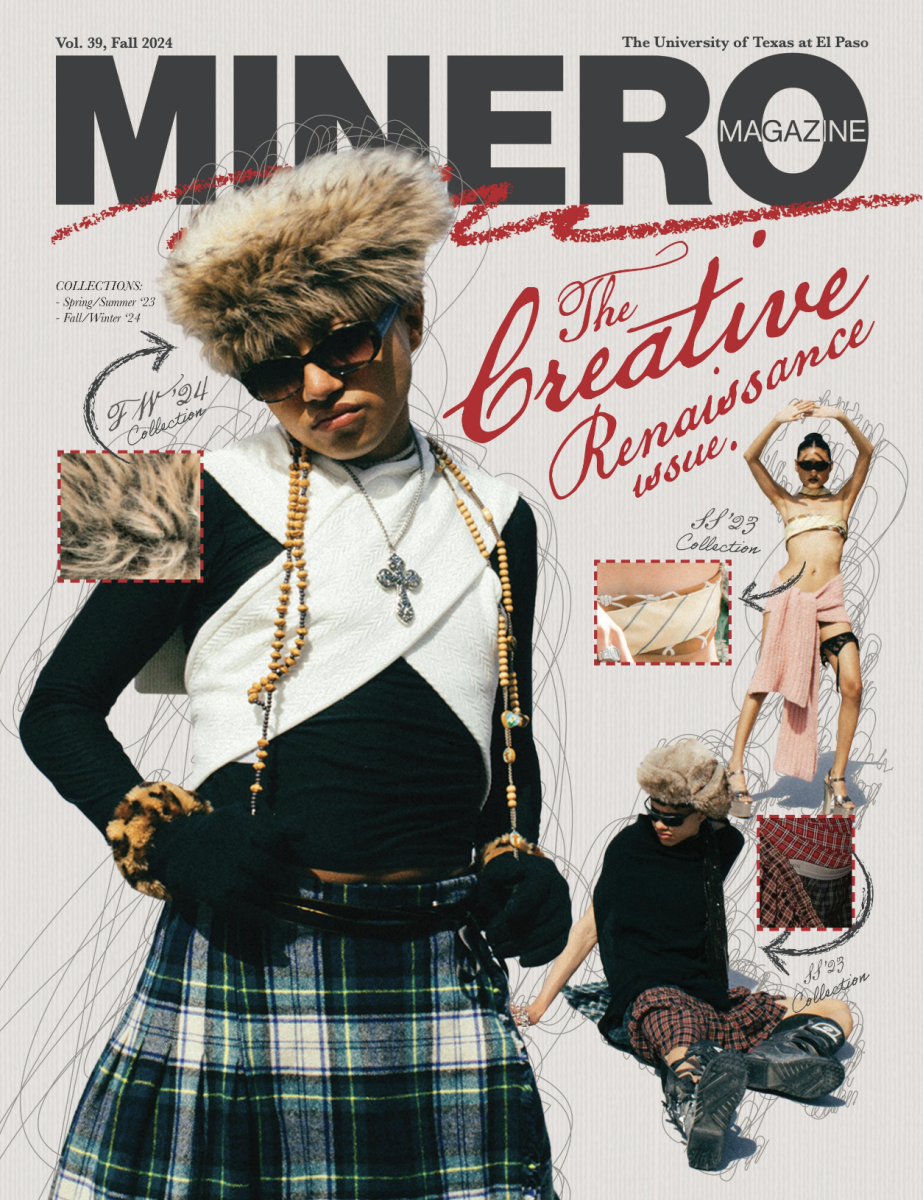

Timeless fashion portrays respect and pride in being Mexican American

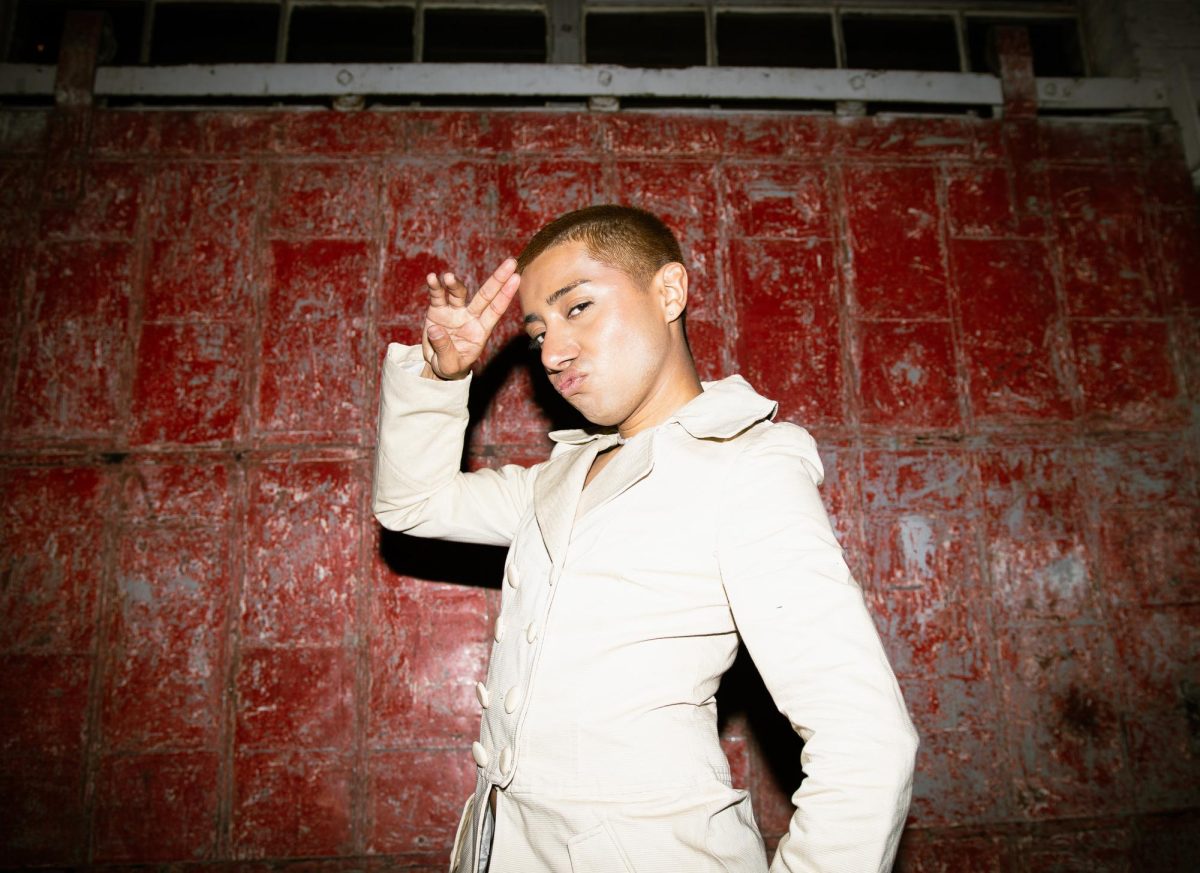

The pachuco of the 40s stood tall, dressed in a long, pressed shoulder-padded blazer that drapes over long tapered pants synched at the waist, and a wide brim tando hat made of wool. To the typical patriotic whites of the 1940s, pachucos were seen as vatos locos, cholos or hoodlums, but to fellow Chicanos along the border, they were a visible symbol of cultural autonomy, wearing a suit of resistance at a time when it was difficult to be anything other than Anglo.

The identity was created in the 1940s and people most associated it with Los Angeles. Made famous by the Zoot Suit Riots during WWII, the style was birthed as resistance to the government garment policy restricting the use of wool and other heavier materials.

The otherwise voluminous style that transformed throughout the decades went from a tailored and classic look to a more casual, cholo style around the 70s and slightly waned in the more modern times. What has stood the test of time is the foundation of respect, the caló, meaning pride, in Mexican American culture molding the generation into what it is today.

Chicanos created their own language, speaking interchangeably between English and Spanish–often in the same sentences–adopting the customs of their parents and mixing these with their new surroundings on the American side of the border.

“I think it was a symbol of a unique, hybrid identity. It’s this mixing of this part of my culture with this nationality that I’ve been given by my parents,” says Chicano Studies professor Irma Montelongo.

That’s when the term “Pachuco” began to identify with much of the new Chicano generation. While no one really knows where the term “pachuco” came from, many believe that it is El Paso who birthed the name. Montelongo thinks that “pachuco” is associated with El Paso because she remembered growing up with family traveling to the borderland.

“A tía or tío was always coming ‘al Chuco,’” she says. Montelongo relates that to other families who moved to L.A. for work during WWII during the 40s. She also mentions “pachuco” came from the city of Pachuca in Hidalgo, México.

“It’s really about culture, it’s about who you represent—your history, roots and where you’re from; It’s all about respect,” says Yvonne Patino, president of the non-profit organization 915 Pachucos & Pachucas Unidos.

There is a general misunderstanding to what pachucos represented. With portrayals of gang members or general troublemakers, she says that she is thankful to dispel those false notions with the community work the organization does.

“Once you put on that tacuche (Pachuco clothing) and that flower in your hair, it’s about respect for yourself and the Latino and Hispanic community that you are helping,” Patino says.

Formed in 2016, the organization’s mission is to support from Anthony to Las Cruces, and then El Paso areas in times of need through fundraisers, clothing drives for local shelters and overall support in the community. With 11 members, including the youngest member being Patino’s eight-year-old son, the group makes frequent appearances in the community dressed as Pachucos.

The pachucos of the 40s created an avenue for their own identity– often, these people were first-generation Chicanos living in a new country. Not quite being American enough for the Anglos because of the color of their skin and different upbringings, they also struggled with not being Mexican enough for México. They had an opportunity to blend the customs from their parents and the new customs of a new country. Creating a pocho, or Americanized, identity to fit their experiences.

“I don’t think the pachucos realized at the time how iconic they were going to become to future generations,” Montelongo says.

As Chicanos participated in the civil rights movement and fought for better education and equality, the overall attitude or orgullo in brown pride evolved. There was power in the uniform of the Brown Berets that was accompanied by a strong motivation for equality and voice for the farmworker, the student who needed education reform, Chicanos and other minorities who faced police brutality.

The next generation of Chicanos transformed into the cholo style that is most recognized today: long-sleeved flannel shirts buttoned to the top, oversized kahki Dickie’s creased to perfection cropped below the knee exposing long white socks and crisp Nike’s classic Cortez shoes. There was no doubt that the style had come a long way from the pachuco style, but kept the clean, classic look. Keeping the attitude from the pride that came from the pachucos and the activism of the Brown Berets, the 70s cholo held a strong sense of identity and Latinidad.

“It’s almost like a genealogy that the 70s cholo was the grandson of the pachuco and the 2000s cholo is the grandson of the 70s cholo and because the attire evolves,” says Montelongo.

In contemporary generations of Chicanos, like Patino’s son, there is a lasting pride in roots. According to a Pew Research Center study, 82% of Hispanics say they are both proud to be Hispanic and American. Recognizing and honoring their Mexican origins, many Mexican Americans said that they prefer to identify with their family’s country of origin to describe themselves; Mexican, Cuban or Dominican, for example.

As style has made its’ own evolution, the caló of la raza hasn’t faded, it has ingrained itself in who we are as another dentity of people of color.

By Jacqueline Aguirre