A bone, sticking through his skin, is what Dawn Hearn, the Director of Sports Medicine at the University of Texas at El Paso, says she saw.

“I saw it happen because it was kind of close to our sideline. He knew something bad happened,” Hearn says. “Well, I couldn’t go out there because they were running this way, y’know? The play is still going on. Then he sits up. He sees it´s not sitting real pretty and he lets out a scream and then, of course, the play is over, everybody sees it,” Hearn

says describing the injury of a past UTEP football player.

This is exactly what happened to Kevin Ware, a Louisville basketball player, who according to an ESPN article posted at the time of the injury, had a break so “awkward” and “frightening” that CNN stopped showing replays.

“I learned from Fred (Hina, the Louisville athletic trainer working the game). Throw a towel over it so nobody can see it,” Hearn says.

And that’s how it’s done. Whether it’s a compound fracture, homesickness, or something as simple as not having enough free time, it seems that all athletes just ‘put a towel over it’ and pretend they don’t see it.

Sophomore Emilio Rios, a jumper for the UTEP Track and Field team, says the workload starts the day you first play.

“When you’re getting recruited in high school, they ask you all these questions that are for people like seniors or juniors who would need to know. Like, I’m a freshman in high school, I just got there and they’re already asking me, ‘what major are you looking into?’” Rios says. “Like, I don’t know. ‘What kind of school are you looking into? Are you looking into D1? Are you going to want to do Junior College (JUCO) first?’ Stuff like that. In that aspect, I had to grow up faster.”

For UTEP’s football players, having little to no free time might mean just putting their mental health on a back burner as school and sports tend to come before anything.

“During my earlier years, in the middle of it, it was tough,” UTEP Football Senior and Wide Receiver, Kavika Johnson, says. “From five, we practice all the way until 10:30 a.m. Then we have weights after that and then we got class. Then, we have tutoring…and it’s all mandatory.”

Not only does it seem that athletes have no time to think for themselves, in some rare cases it might even be hard to find time to eat.

“Everybody starts class 12 a.m. to like 8 o’clock at night so, like, it’s hard to find room in there to eat and stuff. It gets hectic like that,” sophomore Football Wide Receiver Justin Prince says.

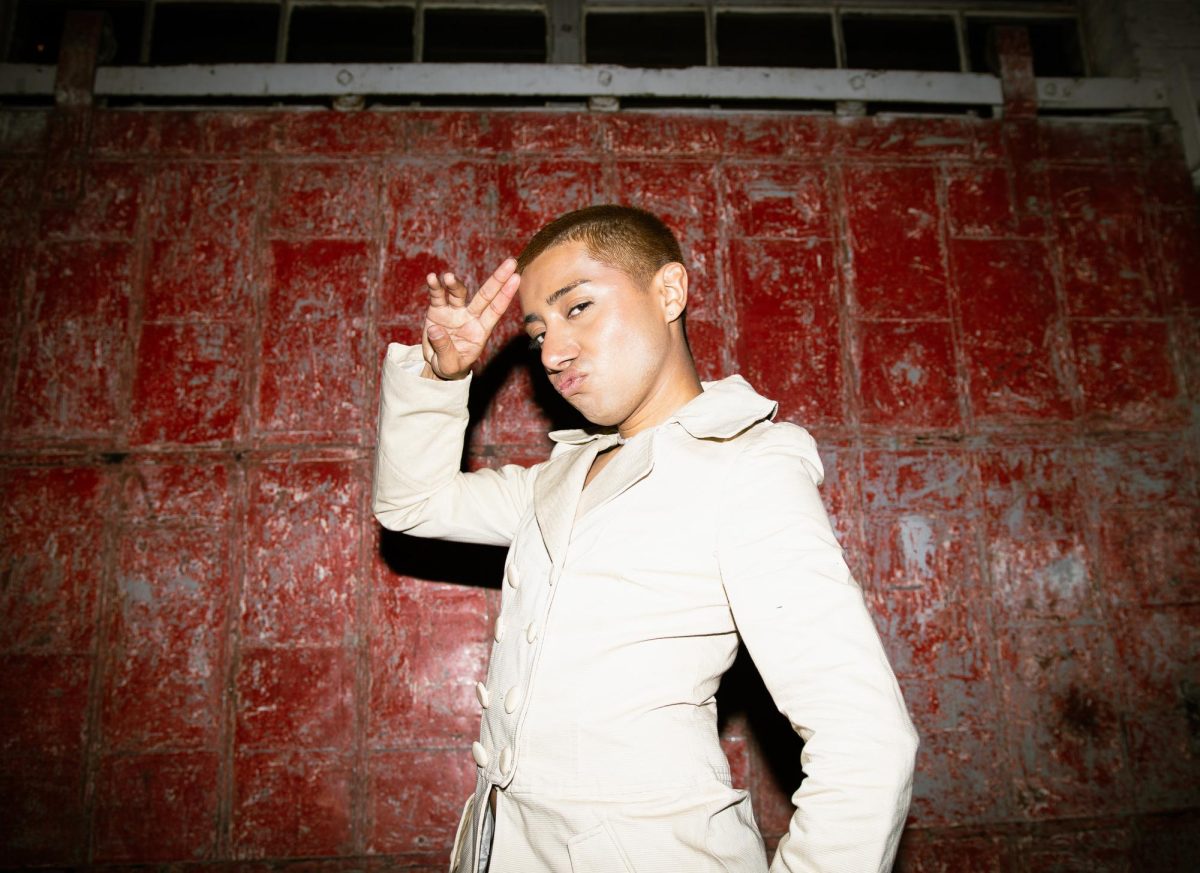

Kavika Johnson

Johnson was born in Ohio. In some sense, he has always been familiar with the hectic nature of the football life, always moving from state to state, living wherever his father Shaun Johnson’s job took him.

Johnson’s dad is a collegiate football coach for New Mexico State University with previous coaching experience in institutions such as Brown University and Utah State. Wherever Johnson moved, whether it was Oklahoma, Boston, Rhode Island or even Colorado, football was what stayed consistent in his life.

“It’s what I’ve been doing since I was a kid,” Johnson says. “It’s different for every athlete. But, my pops, he kind of— he was there to push me, but he wanted to see if I wanted to do it myself. If I wanted to do something and I wanted to be great at it, he was there to push me.”

Just recently, Johnson took on his first job at a local El Paso bar, College Dropout.

“I needed a little extra money,” Johnson says. “I get there and I kind of like just apply what I learned in sports like working fast and efficiently.”

Johnson says despite barely starting to expand his resumé, he’s grateful for the values that participating in sports has instilled in him.

“Sports has given me an opportunity to showcase my abilities that some

people don’t have. I like competing just in general, it doesn’t matter what I’m doing,” Johnson says.

Yet, he admits, during the football season, it was difficult. He didn’t really get time to himself.

“Of course, you get to go home and sleep and stuff. But, during those three months, it’s kind of just all football,” Johnson says. “It does get hectic. Some guys can’t deal with it.”

According to the Journal of Mental Health, college athletes in active

competition tend to neglect mental health to avoid being perceived as

weak. In the 2016 article: Predictors of perceptions of mental illness and

averseness to help: a survey of elite football players, it states that athletes

go as far as ignoring symptoms to “avoid exclusion from practice or competition, especially if they are penalized for taking time off to address mental health needs.”

“I just want to be great so bad in what I’m doing. Sometimes I can’t sleep, I’m always thinking about what I’m doing to get better. I put the most pressure on myself, you have to come ready to work every day,” Johnson says.

Jackie Soto

Junior Jackie Soto started playing soccer when she was 8 years old. She says her sister, who also played soccer in her college years at the University of the Southwest in Hobbs, New Mexico, is someone who she really looked up to and partly contributed to Jackie’s interest and eventually passion for the game.

“We were both brought up to be hard workers,” Soto says. “Soccer is not an easy sport, it’s really competitive. So, it’s something that you always have to work really hard to be good at.”

Soto came on to UTEP’s Division 1 soccer team as a freshman, starting 9 times her first year.

“Physically and mentally, it puts a lot on your body. You’re constantly running in the sun, it’s hard. Sometimes you want to give up because your body is so tired,” Soto says.

That’s where the competitive mentality meets the physicality of athletics.

“Telling yourself not to give up, to keep working— you definitely need to have a tough mentality. You’re playing people just as good as you or maybe even better,” Soto says.

The soccer team, during the fall semester, works 20-hour weeks. Practice in the morning, lifting at 6 a.m. and then another practice around 8 p.m.

“We’re not allowed to schedule our classes before 11 a.m.” Soto says. Usually, the team is able to finish up and get ready for school by noon time.

“That’s what a day looks like— training, school, going to tutoring and then go to bed, rest and same thing the next day,” Soto says.

Soto admits that sometimes it can be tiring to manage both school and sports but for her, it rarely happens. By hanging out with friends and binge watching her new favorite show “Dead to Me” on Netflix, she manages.

“If I’m feeling overwhelmed, I can hang out with my friends that I met in high school. I’m from El Paso so I can see them and I don’t have to be within the athlete community all the time,” Soto says.

Soto’s friends provide a positive atmosphere and words of encouragement whenever any of them are in need and often times find themselves to be reliable and there for each other whenever they need it.

“They always support me. They know what I go through, having to deal

with school and soccer. They’re very supportive,” Soto says.

Milo Rios

Rios, the oldest in his family, is the first to go to college. Getting to participate in track and field at UTEP wasn’t a question for him. It’s something he knew he was going to do the first day he set his mind to it.

Rios’ mother was born in Ciudad Juárez and his dad in El Paso. The pair had him at 17 and 18 years old. The family moved to California until the cost of living got too high, then they moved back to El Paso. His parents’ pasts and beginnings are what ultimately motivates him.

“To be a student athlete, it’s a lot. It’s unrealistic. It takes a special person to have a high GPA as a student athlete, y’know? In a way, it’s kind of irking that you hear people complaining about work and school,” Rios

says. “Like, with those, you choose your hours and with us, like us athletes, we don’t get to choose.”

Rios has been playing sports ever since he was a little kid, but didn’t take it seriously until high school.

“I kind of had to isolate myself,” Rios says. “Not everybody had the same mentality or they don’t understand what that mentality is. So, I tried to surround myself with people on that same level.”

That means, for Rios, anyone who wasn’t in any athletics, weren’t included.

“I call them NARPS, Non-Athletic Regular person,” Rios says. “It was a help each other type-of-deal. Like, you help me I help you. Then it becomes one of those things where like, if someone doesn’t understand why you’re acting that way then, yeah, it affects you.”

“The pressure gets to everybody,” Rios says. “That’s just human.”

Sky Estrada

“You have class, you have your weights, you have conditioning, you have

treatment, then you have study hall and then you try and fit in bits and pieces of me time. So, there’s so much pressure leading from everything, you know?” sophomore softball player Sky Estrada says.

“So, ultimately it’s a lot. Sometimes, if you don’t have an outlet to put that

pressure in, it can be detrimental to a person and ultimately it can end up in a break down and then you’re just crying in the shower,” Estrada says.

According to the International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, physical stress/injuries and psychological stress can impact athletic performance and hinder training, career transitions, interpersonal functioning, and physical rehab unless properly treated.

Additionally, the journal reports that 21% of male and 28% of female collegiate athletes had experienced depression to the point of impaired functioning. These effects, according to the journal, are associated with severe injury, surgery, life events and a higher level of career dissatisfaction or a lower level of social support.

Estrada was born and raised in El Paso and chose not to leave so she could stay closer to her family. The young softball player, who texts her mom every day about topics ranging from the poodle walking on the sidewalk to the details of her long and strenuous day, feels that her family is a strong support system to get her through the tough times. Yet, there are still some things that she feels she still cannot share with them.

“You never want your parents to think that you have something wrong with you,” Estrada says.

Estrada, whose family, she says, is well known in the El Paso softball community, has surrounded herself with softball ever since she was 2 years old.

“My first memories are of swinging a bat,” Estrada says. “Like I don’t know how to swim, I don’t know how to ride a bike, but I know how to swing a bat. That’s my life.”

Estrada’s dad played baseball at Sul Ross. Because of this, she felt that there was a lot of pressure to perform well and keep playing the sport.

“If I didn’t play then, I was the black sheep,” Estrada says.

Her parents, who she says built themselves from the ground up, believe in hard work and were pushed to do a lot as kids. According to Estrada, she feels that her parents push her to have high expectations for herself as her parents have likewise held for themselves.

“Sometimes I would break down and cry and wonder why me, but there were other days where I said: there’s other people who have it worse,” Estrada says.

“I feel like the mentality that I have is just to keep going. If I listened to what people told me, I definitely would not be in the position I am today.”

Estrada recalls hearing things like: you’re too short, you’re not fast, you’re not strong, and there’s no way you can compete at this level. She said she could never see herself talking to her parents about these types of things and feelings.

According to research observed by the Indiana Law Journal, between 10 and 15 percent of student-athletes “experience psychological issues severe enough to warrant counseling.” Yet, as stated in the same journal, student-athletes are less likely to seek professional health.

“I never wanted them to see me at my weakest and I think that

goes for every kind of athlete and every kind of kid,” Estrada says.

More often than not, Estrada finds herself reaching out to close relatives and friends when she needs someone to talk to.

“I spend time in my room watching Netflix, reading. I have a boyfriend who lives like 8 minutes away so it’s easy for me to go visit him. I also like to color. It’s like so therapeutic,” Estrada says.

At UTEP, there are resources for athletes who might need to seek help.

Besides teammates, family or friends, the university’s athletic department offers general counseling services. “These services offer a wide variety of counseling that vary from alcohol and drugs or any other services that an athlete might need”, Tony Cordova the Associate Director of Sports Medicine and Head Athletic Trainer for Football says.

By Brandy Ruiz

En Breve

Un hueso, fuera de la piel de un atleta, es lo que Dawn Hearn, directora de medicina deportiva en la Universidad de Texas en El Paso, dice que vio.

“Lo vi porque estaba cerca de nuestro lado. Él sabía que algo malo había pasado”, Hearn dice. “Entonces no podía ir ahí porque estaban corriendo hacia este lado. El juego seguía. Entonces él se sentó, se da cuenta que no se puede sentar bien y grita. Hasta ese momento pararon el juego y todos lo ven”, Hearn dice, describiendo la herida de Kevin Ware, jugador de basquetbol en Lousville.

Según un artículo de ESPN, Ware tuvo una fractura tan “incómoda” y “aterradora” que CNN dejó de repetir la grabación.

“Aprendí de Fred (Hina, entrenador de Louisville que trabajó durante el juego del accidente). Tienes que tirar una toalla sobre la herida para que nadie la vea”, Hearn dice.

Y así es como viven lxs atletas, ya sea con una fractura compuesta, extrañando su hogar, o algo tan simple como no tener tiempo libre. Parece ser que lxs atletas colegiales no tienen un respiro. Las obligaciones de pertenecer a un equipo van más allá de simplemente jugar.

“Era duro al principio”, dice Kavika Johnson, receptor en el equipo de futbol americano de UTEP. “Desde las cinco, practicamos hasta las 10:30 a.m. Después tenemos pesas y luego vamos a clase. Después, tenemos tutorías…y todo es obligatorio”.

Milo Rios, quien entrena atletismo en UTEP, dice que ser un estudiante atleta “es mucho”.

“Ser un estudiante atleta…es poco realista”, Rios dice. “Se requiere ser una persona especial para tener un GPA alto como estudiante atleta. En cierto modo, es algo irritante cuando escuchas a gente quejarse del trabajo y la escuela. Con ellos, tú puedes escoger tus horas de trabajo. Con nosotros, tú no puedes escoger tus horarios”.

Johnson, dice que a veces es difícil porque no tiene tiempo para sí mismo.

“Claro que cuando puedes irte a casa, puedes dormir y así. Pero, durante esos tres meses (de temporada), solamente es futbol”, Johnson dice. “Si es frenético. Algunos no lo pueden sobrellevar”.

Según el Periódico de Salud Mental, lxs atletas universitarixs descuidan su salud mental para evitar ser percibidxs como débiles. En un artículo llamado Predictores de percepciones de enfermedades mentales y aversión para ayudar: una encuesta a jugadores de fútbol de élite, dice que lxs atletas incluso ignoran síntomas para “evitar la exclusión de la práctica o competencia, especialmente si son penalizados por tomar tiempo fuera de práctica para atender sus necesidades de salud mental”.

Para Sky Estrada, jugador de softbol en UTEP, su familia forma parte importante de su rendimiento como atleta.

“Nunca quise que me vieran en mi punto más débil y pienso que eso aplica para cualquier atleta y cualquier niño”, ella dice.

Jackie Soto, futbolista en UTEP, admite que a veces puede ser exhaustivo manejar las responsabilidades de escuela y deporte, pero para ella, muy pocas veces sucede. Ella trata de pasar tiempo con sus amigxs y ver series en Netflix para relajarse.

En UTEP, hay recursos para lxs atletas que puedan necesitar ayuda con su salud mental. Aparte de otrxs estudiantes atletas, familia o amigxs, el departamento atlético de UTEP ofrece servicios de terapia general.

By Brandy Ruiz