By Andrés Rodríguez

By Andrés Rodríguez

Léelo en español

The school year just started and Zachalyn Elizares is moving to Hawaii. Her daughter refuses to return to Andress High School, so her and her brother have already left, while Zachalyn remains in El Paso taking care of the last details of the move.

It’s been three months since her son, Brandon, 16, committed suicide, and Zachalyn prepares to take on the subject outside of the main room at Desert View United Church of Christ where Parents, Family and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) El Paso meets every month and where, after the session, she’ll talk about her experience as the mother of a bullied child.

“Kids got picked on for all kinds of reasons, but my kid got picked on because he was gay,” Zachalyn says before getting up to speak—her son was bullied by his classmates for at least two years at Andress and Chapin high schools after coming out as gay in 2010. “He didn’t get picked on because he had on shoes that somebody else didn’t like…and that’s a very clear difference.”

Zachalyn Elizares talks about the bullying of her son, Brandon.

According to the National Youth Association, bullying is two to three times more likely to happen to members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered and queer community than it is for heterosexual individuals.

Brandon committed suicide June 2 in his North East El Paso home, after his bully challenged him to a fight the following week. But his mother says that the bullying was something that constantly affected Brandon, even though he didn’t always show it. “Clearly he had problems, but the problem was that at the time of his passing he seemed happy on all accounts. From his therapists and his councilors and all the outside sources, he seemed happy.”

After Brandon’s death, PFLAG got involved, and after discovering that the suicide was due to bullying, they formulated a plan to put in place procedures to prevent bullying in schools. “Over the summer, Brandon’s family, PFLAG and part of the El Paso ISD school board worked closely in developing a new anti-bullying policy and that policy included LGBT kids,” says Daniel Rollings, PFLAG El Paso president. “Prior to that they were never mentioned by name…now they very specifically cannot bully someone based on their orientation or their gender identity, and it’s not only the actual identity but the perceived identity.”

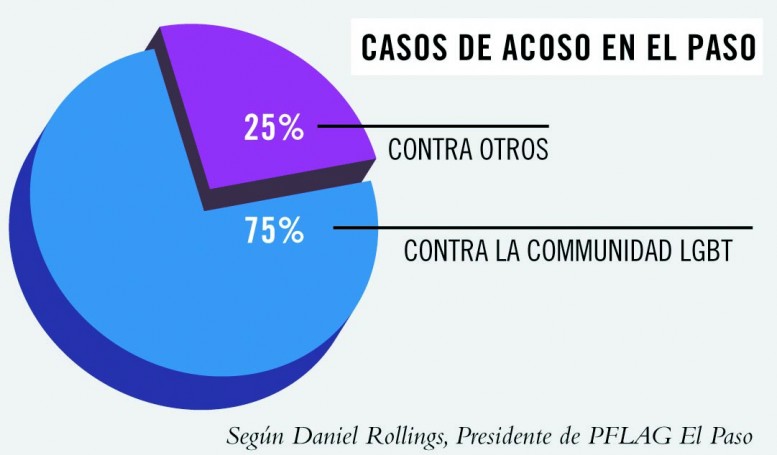

Rollings says that three-fourths of all cases of bullying in El Paso are directed against the LGBT community. Which is why, he adds, PFLAG organizes support groups across the city that focus on gay and straight alliances in high schools, transgendered individuals and support to the bilingual community in LGBT issues.

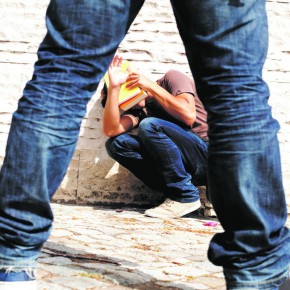

For some, bullying comes from multiples aggressors, both in the classroom and at home. For Jessica Garcia, for example, bullying brings to mind two things—the bullying she received from a schoolmate in high school and the bullying she received from her mother after coming out as a lesbian.Watch Full Movie Online Streaming Online and Download

Jessica, a senior psychology major at the University of Texas at El Paso, and her bully, Abraham, lived in the same apartment complex, went to the same school and shared the same friends. “I remember I hated the walks home,” says Jessica, who was 15 at the time. “He would always follow me home and start calling me names from like the time the bell rang all the way to my house, which took like 20 minutes…He would always refer to me as tomboy or he would call be dyke and different names that are demeaning to somebody who’s gay and I didn’t even know what those terms meant.”

Jessica estimates that her Riverside High School schoolmate bullied her for seven or eight months. She never asked for help, as she says she was afraid that she would be rejected by her friends and family.

Tired of the insults and the intimidation, Jessica confronted Abraham. “I just hit a point when I said enough is enough. This guy is changing my life. I feel like I’m secluding myself because I’m scared of him…(I) told him to stop calling me those things,” Jessica says. “Frankly I thought that he was going to beat me up…because I heard that he would beat up his girlfriend. He just kind of brushed it off, laughed a little and actually stopped after that.”

Although the bullying never escalated from there, Jessica says it has to be taken more seriously. “People don’t realize how bad it can impact somebody. How bad it can make you feel, kind of feeling ashamed of how you look. You kind of want to hide it a little and suppress it,” she says. “It can be heartbreaking, especially when you’re at that age when you’re a teenager and you’re trying to find out who you are.”

Then, after coming out to her mother, Jessica says she was rejected again. Her mother told her she had to leave the house after failing to turn her straight. “I bounced around and I finally turned 18. I got myself a job and I was starting college here. I was totally not motivated to be here because I just fell into a deep depression,” Jessica says. “Mostly everything that I did, I had to do it on my own. I had to make my own decisions. Had to be tough on my own…I didn’t have a choice.”

Jessica Garcia thinks more can be done to prevent bullying.

Similarly, Elizabeth Polinsky says she was rejected by her church. Claiming that she was emotionally unstable, Elizabeth was fired from her job as a youth pastor, which she had held for two years, after one of the parents of her youth group saw her kissing her transgendered boyfriend on the cheek.

“(The pastor) talked to me…and told me that he knew about my boyfriend,” says Elizabeth, a senior linguistics major at UTEP. “(He) told me that I wasn’t allowed to spend anymore time with my youth kids anymore.”

However, she was not fired immediately; instead, her church had her do administrative tasks and meet with individuals to treat, what they thought to be, a trauma.

“They thought that I’d just had terrible experiences with men and that that’s why I could ever be attracted to someone who is transgender. And they couldn’t decide if I was a lesbian or not and it didn’t really matter what I had to say, they kind of just told me that I was a lesbian and that I needed to not be attracted to girls,” she says.

While she attended the prayer sessions, Elizabeth took a medical leave from the university because she says she couldn’t function during class, and then she began to think about suicide after seeing her community at church turned against her. “It’s very rough when you have been with a church for so long and you have very close relationships with them and they kind of turn on you,” Elizabeth says. “People were telling me that I wasn’t actually a Christian…(even though) I’ve been here this whole time.”

Elizabeth began going to counselors to treat her depression because she says thinking about suicide scared her. Now, two years later and working for Miner Rainbow Initiative, a university organization that seeks to establish a safe and accepting environment for the LGBT community at UTEP, Elizabeth considers her experiences to be bullying. “I don’t know what else it would be,” she says. She also thinks that bullying against the LGBT community resides in conservative places like churches and that it is perpetuated because people, like her, leave and don’t come back to teach those who oppose their lifestyle.

Elizabeth Polinsky on why she stayed at her church before she was fired.

Community Support

The El Paso Sheriff’s Office Anti-bullying Coalition along with PFLAG conduct programs to deal with bullying. Last summer, PFLAG El Paso began an internship program in collaboration with UTEP’s social work department, in which interns gave classes at schools about safe zones. Interns are also in charge of the three support groups across the city.

Alexis Alvarez, senior social work major at UTEP, is one of the three interns. She is in charge of the transgender support group, which meets once a month. Alexis says that her objective is to build a community for transgender individuals because she says the city is missing one. Her and the other two interns are working on a project to assign safe zones at schools. “We are working on the safe zone project, which is in memory of Brandon Elizares,” she says. “We came up with a presentation and we’re actually presenting that at EPISD to all the faculty and teachers, and it’s kind of like a training on bullying and why it’s important and how to stop it.”

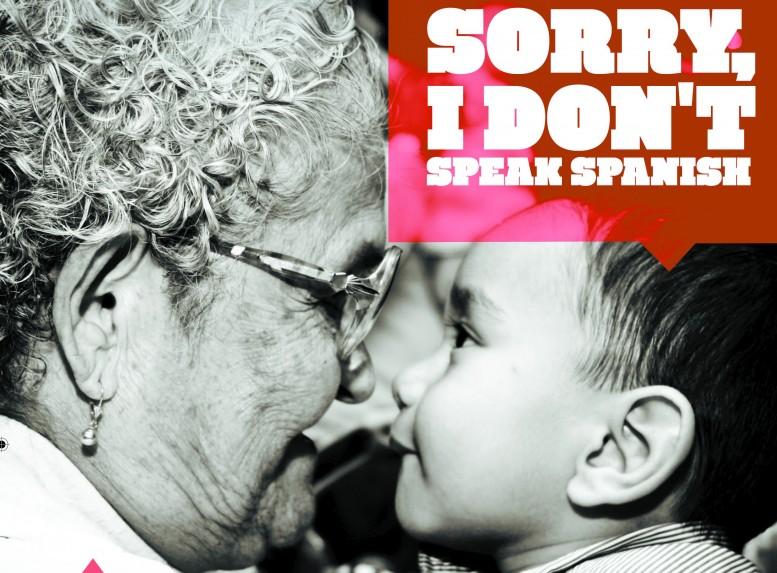

Roxana Romero, senior social work major at UTEP, is in charge of the bilingual support group, which focuses on topics that relate to LGBT issues on the border.

For Roxana, who volunteered at PFLAG for two semesters before becoming an intern, the advocacy is what most caught her attention. She was involved in cases where transgender individuals, one a man-to-woman, the other a man-to-woman, were discriminated against by their schools. A transgender 5-year-old girl was not allowed to use the women’s restroom at school, and a young transgender man was not allowed to walk the stage during graduation in a suit. PFLAG took on both cases. “That’s exactly what I love about it,” Roxana says. “That it stands up for equality; no matter what your situation is you have equal rights or you’re supposed to have equal rights, which is sometimes hard in this community.”