By Guerrero Garcia

Léelo en español

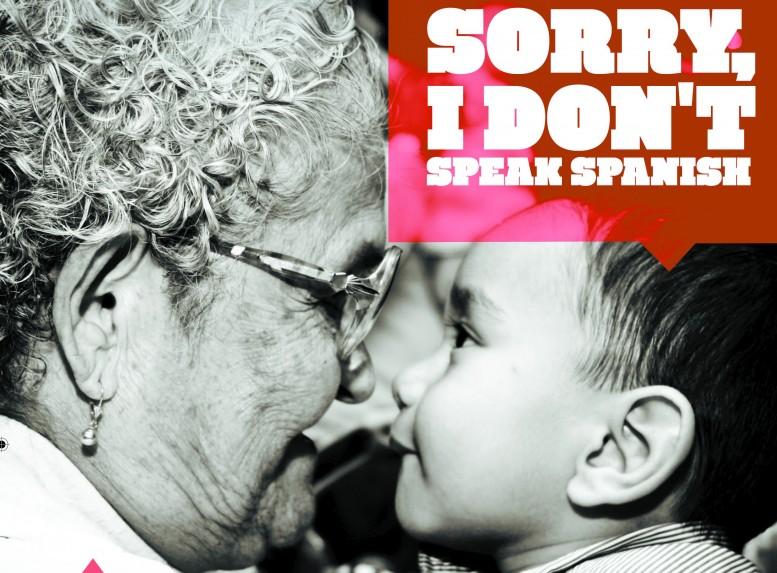

Brian Garcia and his grandmother sit at the kitchen table to share a meal, caldo de res con arroz y tortillas de maíz (beef soup with rice and corn tortillas). The steam from the soup evaporates as his grandmother gives thanks and blesses the food. While they eat, the only sounds echoing in the room are that of the silver spoons clashing the bowl and the slurps as they sip the soup. Brian and his grandmother sit close together, legs touching, yet they seem distant—the barrier between them is language.

Brian is a junior criminal justice major at the University of Texas at El Paso and a second-generation Mexican-American who only speaks English. This makes it difficult for him to speak to his grandmother, a Mexican native and Spanish speaker. “I feel embarrassed when trying to speak Spanish with my grandma,” he says. At a young age, Brian spoke Spanish, but he got to a point where he just stopped speaking it. “I don’t remember how old I was, maybe 7, but it was not spoken as often at home or at school…I understand some words, but when I try speaking it, I can’t put words together, the pronunciation just does not come out.”

The U.S. 2010 Census indicates that 72.8 percent of El Paso’s population speaks Spanish at home, a result of the city’s demographic profile—where more than 600,000 are Hispanic or Latino. In the United States, the Mexican-American population is surpassing 50.5 million as reported by the U.S. Census, and in about 10 years, more than 60 percent of all U.S. teens will belong to the Mexican-American and Latino population.

In El Paso, the city’s proximity to Mexico has allowed the culture and language to migrate across the border fence, but younger generations born to Mexican-American parents are experiencing Spanish fluency loss.

“Spanish, in many ways, is challenged by American institutions,” says Howard Campbell, professor of anthropology at UTEP. “For anyone to succeed economically and socially in this country, especially young people, English is so indispensable.”

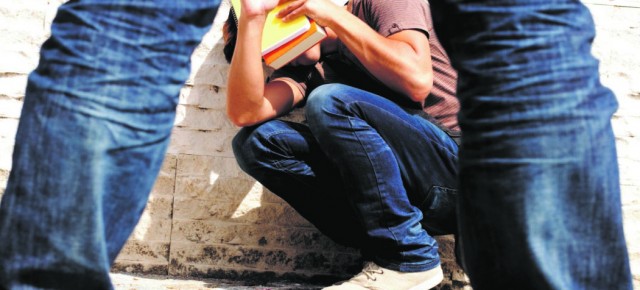

Like Brian, many other Mexican-Americans from the El Paso area have unconsciously chosen English as their primary language, leaving their first language of Spanish behind at a young age. Factors such as the early educational systems, parental influence on language and popular culture attribute to the challenge of retaining the Spanish language among the Mexican-American youth.

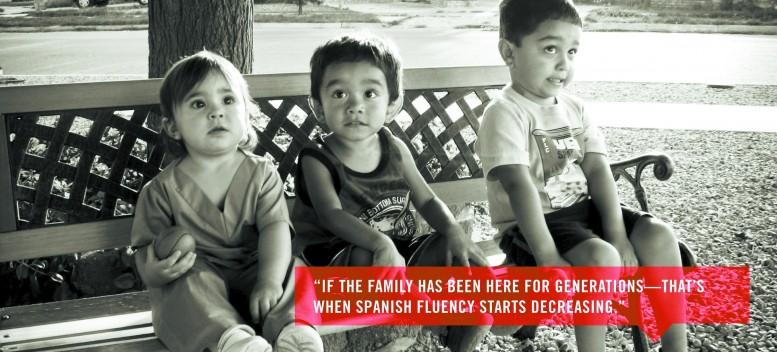

The results of The Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study conveyed that 17 percent of third-generation Mexican-Americans speak Spanish, while 5 percent of the fourth generation speaks Spanish. Campbell describes the absence of a mother language in upcoming generations as a form of assimilation. “By and large in the United States, it is the pressure of the American culture that forces Mexicans or Latinos to ultimately make English their first language,” Campbell says.

He credits the preference of the English language among the youth in El Paso to be inevitable because of the fact that it is all around them. “We have to be realistic—Spanish is confronted by American popular culture. English is needed in the school systems, in getting a job and in terms of their social identity and their social lives,” he says. “Students may speak Spanish at home with their family, which is usually the case for second and third generations, but ultimately it begins slanting to English.”

English is introduced during the early levels of the American public education system, which plays a role in Spanish fluency loss among young Mexican-Americans. In elementary school programs, Spanish speakers are transitioned from speaking Spanish to speaking English. Matthew Castro, a second-generation Mexican-American, grew up speaking Spanish at home, but at an early age was transitioned to the English language. “I grew up speaking Spanish, but probably when I was 6 or 7 years old, I started to pick up English,” he says. “School was probably the reason why I stopped talking Spanish.”

Matthew, a sophomore mechanical engineering major at UTEP, says that when he entered the school system, he was placed in bilingual classes, but later was placed in English-speaking classes. “When I went to school, we had the bilingual classes for those who spoke mostly Spanish, and for everyone else who spoke English, they were put in regular classes,” he says. “When I was placed in a regular class, everyone around me spoke English.”

Surrounded by the English language, Matthew was forced to leave his native language of Spanish behind and pick up the language that was spoken on the playground, in the cafeteria and in the classroom. “I don’t really speak Spanish fully anymore,” he says. “I struggle at times when I try speaking it, but for the most part I understand basic words.”

Heriberto Godina, associate professor of teacher education at UTEP, has worked with young students in public schools and has been exposed to some of the programs. “It’s a hit or miss with American schools,” Godina says. “Some schools do a very good job of promoting bilingualism, but others suppress the Spanish language, this can be detrimental for the kids.”

He says that school districts in the El Paso region such as Ysleta, whose Mexican-American and Latino student population is as high as 86.1 percent, according to a summary report to the Haynes Foundation, implement dual-language programs. “Schools in the Ysleta, Socorro and Canutillo districts do a good job in advocating for bilingual education programs,” Godina says. “They know bilingual education works. That is why they promote it.”

While some schools in El Paso do endorse bilingual education, Godina believes it has a small influence on the role of Spanish loss among young people. “To be honest, what I really see is young people being motivated by popular culture,” he says. “It is who they hang around with, what television shows they watch and what music they listen to that has students retreat from the Spanish language.”

Brian recalls being in elementary school and gravitating to the English language because of his peers. “I had my Spanish-speaking friends, but when I was placed in an English class, I began making English-speaking friends,” he says.

Carlos Ortega, lecturer in Chicano Studies at UTEP, says the exposure to American television shows and popular music also plays a role in Spanish fluency loss. “Musically, Spanish loss can be affected by the memorization of the lyrics,” he says. “One hears the lyrics in the English language, and one can easily start thinking along the lines of the lyrics weakening their use of Spanish.”

Ortega also says parents have a great influence on the child’s ability to retain the language. Both Brian and Matthew were raised speaking Spanish, but their parents did not reinforce the Spanish language at home, which allowed the language to slowly fade. “Some parents will wake up one day saying they wanted their children to learn English, but later on realize that their children needed to preserve their Spanish as well,” Ortega says.

Some Mexican-American parents raise their children speaking only English and never introduce them to the Spanish language. This was the case for Sarah Lopez, a second-generation Latina who was raised by her Mexican mother and Puerto Rican father. “My parents would speak in Spanish to one another, but when they would talk to me they would speak in English,” she says. Sarah grew up speaking English, but picked up some Spanish words from her relatives who came to visit from Mexico. She rated her ability to speak Spanish as very low. “I cannot speak it,” she says. “I understand some of the language, but I will not speak it.”

There are also those parents who choose to instill the Spanish language into their children. Freshmen sisters at UTEP, Daisy, linguistics major, and Jocelyne Gomez, criminal justice major, say they are not allowed to speak English at home, which helps them to preserve the Spanish language. “If we mispronounce a word in Spanish, our mother will correct us and tell us it has to be proper Spanish, she hates Spanglish,” Jocelyn says. The sisters are second-generation Mexican-Americans and are proud to speak both the Spanish and English languages fluently. They credit their mother for her strong belief of keeping their native tongue of Spanish alive. “She wanted us to learn English, but did not want us to forget Spanish,” Jocelyn says.

Forgetting the Spanish language is common among second and third-generation Mexican-Americans because of the power of American institutions and popular culture. In El Paso and in many other areas of the nation, Spanish is decreasing with each succeeding generation. As the population of Mexican-Americans and Latinos in the country is increasing faster than any other ethnic group, it seems that Spanish, although threatened, is unlikely to disappear. “With such a critical mass, it seems likely that Spanish will be the second language spoken in the nation, officially or unofficially,” Campbell says.