By Adrian Broaddus Design by Jacobo De La Rosa Photography by Andres Martinez and Michaela Roman

Pablo, a sophomore student at UTEP, who decided to maintain anonymous slips into his car with a group of his friends seeking a night of adventure, tales and enjoyment. He tells his mom he’s simply going over to a friend’s house to hang out, but Pablo’s mother truly knew what her son was doing on a Friday night, her stomach would churn.

He and four of his friends find metered parking on the outskirts of downtown El Paso, and as they spill out of their ride, they walk to a new journey into the night and into another country. As they trot up Santa Fe Street, the road curves ahead and a large sign shows “Bienvenidos a Ciudad Juárez.”

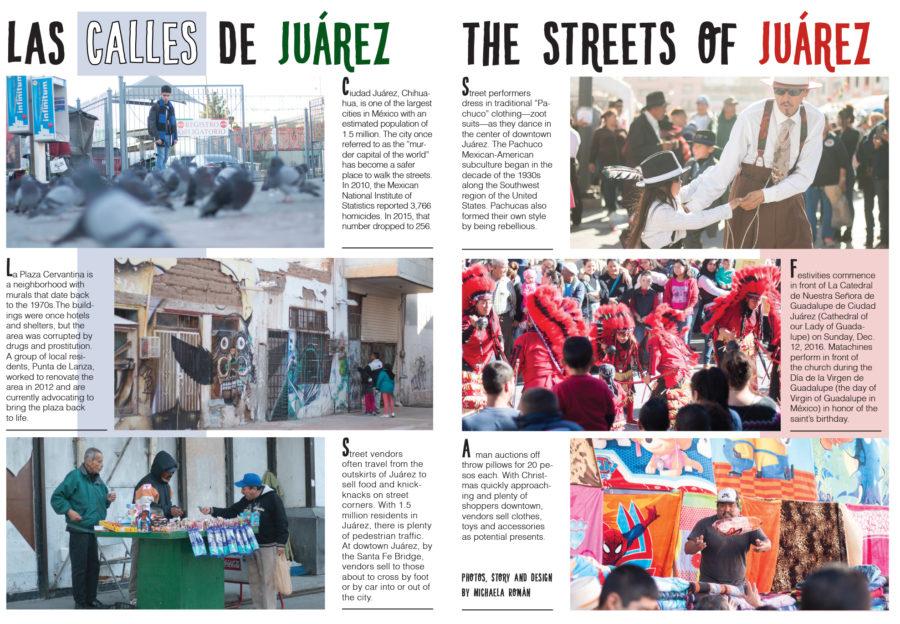

In retrospect, why would any teenager or young adult want to cross into the city of Juárez at nighttime? Less than a decade ago, Juárez, México, was known as the murder capital of the world. In 2010, Juárez had more than eight murders each day, cartel violence flooded the streets, and the entire city was faced with much corruption. Juárez, during 2006, had a higher annual death rate than any other country, including Iraq, Afghanistán and other dangerous countries.

But, as assured by most border-crossers, the city has changed for the better.

“The thought of it being a risk does go through the back of my mind, but it never stops me from crossing over,” Pablo says. “I can see the border from the bar, so it doesn’t feel unsafe.”

Pablo and his friends walk down the right side of the Santa Fe Street sidewalk and approach the U.S.-México border and the port of entry to México. “Cincuenta centavos (50 cents),” mutters the lady behind the glass window at the entrance.

One step through the revolving gate is one step closer to another country.

Immediately to the left are hoards of cars attempting to cross over to the U.S.—lines are extremely long and the traffic is unmoving. Beggars and street vendors flood the street, while window cleaners wipe down car windows in attempt to gain a tip from people passing by.

It’s far different from El Paso instantly. “One of the most noticeable things to me is the fact that there is no border security when you pass over there,” Pablo says. “You can walk past their border patrol without any worries or troubles. In fact, they don’t even look at you.”

They walk down the street amazed at what’s ahead. Two women begging for passersby to stop and buy one of their packages of gum, children running around the street and cars driving with no regard to road signs or pedestrians.

Eyes from the locals scan each member of the American posse, but it doesn’t faze the explorers, they are on a mission for liberation and they are not limited by being underage. México’s drinking age is 18 years old, so the underage kids, who are not allowed to step foot into a bar with the 21-year-old requirement of the U.S., are able to easily and willfully purchase alcohol across the border.

They make their way up to a currency exchange station, where they deposit their money in exchange for pesos. One $20 bill exchanged for more than 18 pesos per dollar ends up being a big chunk of change for an individual. For Pablo and his crew, they combined their money together to take advantage of the large gap in currencies.

“That’s another big reason I go,” says Jonathan Vasquez, a sophomore business major who tagged along with Pablo. “The drinks and food are cheap, so I get my money’s worth. When you can get some drinks, a big plate of tacos and still have money left over, you know you got your money’s worth.” After they have their change in their pocket, the group trots over to the Kentucky Club right along the main strip.

The Kentucky Club has been around since the 1920s and is known to be the birthplace of the Margarita. It is a small cantina bar, which is located next to the Santa Fe International Bridge. The bar is Americanized—American television and sports games are shown on the television, the menu comes in English, and some of the waiters know how to speak English. But it still has the Mexican flavor that Juárez offers.

After ordering a round of Margaritas and Modelo beers, Pablo and the bunch order the Kentucky Plate, which is a platter that offers 12 tortillas, hot wings, ground meat to put in their tortillas, chips and beans.

The plate, which is the size of most tables, fills the bunch with its unique Mexican-style servings. Then, they pay off their tab and are off back onto the streets. A ways down the street, the team finds a small taco spot, which smells amazing and sells inexpensive tacos. They end their journey at a sports bar called the Yankees Bar and then make their way back home.

Scared Straight

While some newcomers enjoy their free-spirited mindset on the city and its nightlife, others take major precautions due to the recent happenings in the city. Junior marketing major Bianca Duran is highly conflicted with the thought of going over to Juárez and is against traveling across the border.

“It’s just a personal preference, but I do have family that crosses regularly,” Bianca says. “I would go often as a kid, but it stopped when the violence began.”

It was the same violence that plagued not only the city of Juárez, but also left emptiness in her heart. “When I was a sophomore in high school, I had a friend that was killed due to the violence and I haven’t gone back to Juárez since,” Bianca says. “My dad has also lost some close friends. I get invited, but I’m very firm in my decision to not go.”

In fact, it is a personal preference that now has a deeper impact, which is drawing her to the city. “I would think of going if one of my relatives was in the hospital—that’s happening right now and I’m very torn about going or not,” Bianca says about her father’s step uncle.

Her personal preference also comes with wise morals she chooses to live by. Duran also provides advice to those who do choose to cross over. “Think twice (when crossing over) because it’s difficult to fully observe your surroundings while sober, much less intoxicated,” Duran says. “Most kids have the mentality that nothing will happen to them until they’re personally affected, like me.”

America-Juarez Frenzy

One of the more popular nightlife attractions, which is known to bring many tourists to the city, is the famous bar The Kentucky Club. With the violence that was going on in the city about a decade ago, the bar, according to manager Alfredo Torres, was close to shutting down due to a lack of business.

“Now there is more tourism and business. We have more people, more Americans and people from other countries and cities in México who come visit,” says Alfredo Torres, a manager at the club . “(During the drug war) there would be about 30 people on a normal night. Now it’s 50 to 200 people. It’s different, better.”

Torres also claims that there are tons of El Pasoans who are normal border crossers who come out to the bar time and time again.

“Mothers can walk around with their children now. It’s such a different sight,” says Carol Hunter, who is an American journalist and a frequent traveler to Juárez from El Paso. “Families would post pictures in honor of their daughter’s quinceañera, a significant celebration in Mexican culture, and the girls would be kidnapped for ransom. Now families don’t have to worry about those kinds of things like before.”

For Old-times sake

For Franklin High School marketing teacher Chelsea Knapp, the fear of cartel violence was never on her mind when she was crossing over to Juárez. Knapp, who was 15-years-old when she would cross over “We would cross over without a thought in our mind,” Knapp says. “There was no such thing as checking our ID or checking our passports. There was only one stop at the border, where you would pass by and say ‘American.’”

There was a sense of unity and respect when they came across. Like those who go over nowadays, Knapp and her posse would hit up bars like the Kentucky Club and Reno’s. They even knew the bouncer at the Reno’s bar, who would help them translate anything they needed, she was like a “Mexican mother” to her group.

“We had Esther’s [the bouncer] cell phone number and we would call her whenever we were on our way to the bar,” Knapp says. “Just five years ago, she got shot and it was a big deal. Reno’s was the place to go.”

In fact, it was Knapp’s “Mexican mother” who helped her and her friends out of a police predicament. “My friend had just broken up with his girlfriend and he was mad so he punched a wall–it was nothing serious, did no damage–but he just punched the wall because he was mad,” Knapp says. “Then, cops came by and found out my friend was American. They told him that either he gave his watch to them or he would be taken to jail. Esther came out and helped translate and resolve the problem, but my friend still got his watch taken away.”

It was because of this instance that Knapp’s mom became aware of what her daughter was doing when she was coming home late at night. “I told my mom and at first she was really mad, but the next day she asked me what I was doing over there,” she says. “I told my mom we went for dinner, and she asked where, so I told her the Kentucky Club. My mom started laughing and pulled out a photo box. In it, she pulled out a picture of my mom sitting in the exact spot that I sat in at the Kentucky, holding a drink that I would order that day from the same drink menu. Now, I hear of students going, and I think back to myself and even back to my mom—those places have been around for all our generations.”

Although she enjoyed her fun in Juárez, Knapp is convinced times have actually changed and she doesn’t believe younger adults should go over, not because of the city, but because they are enabling underage drinkers to make unfit decisions. “The city has it’s ups and downs, but the target market of the Juárez strip is the age group that doesn’t involve the decision-making process for going over,” Knapp says. “As soon as I didn’t need to go over, I didn’t see the reason to go over for anyone. It’s not acceptable, and I sound like my mom, but times have changed.”

En Breve

Hace menos de una década, Juárez, México, era conocida como la capital de asesinatos del mundo. En 2010, Juárez tenía más de ocho asesinatos al día, el cartel y la violencia inundaba las calles, y la ciudad se encontraba bajo mucha corrupción. Juárez tenía en 2006, el indice más alto de muertes anuales en comparasion con otros países, como Iraq, Afghanistán, entre otros países peligrosos. Pero, como lo asegura la mayoría de los fronterizos, la ciudad ha cambiado en una manera positiva.

Pablo, estudiante de segundo año de ingeniería mecánica, quien a decido ser anonimo, en esta historia, sube a su carro junto a sus amigos buscando una noche de aventuras. Ellos estacionan el carro en el centro de El Paso y cruzan el puente Santa Fe. Un dólar vale más de 18 pesos y Pablo y sus amigos terminan combinando su dinero para aprovechar la gran brecha entre ambas monedas. Se dirigen al bar Kentucky Club el cual ha estado desde los años sesentas y es conocido por ser el lugar de origen de la margarita. Mientras algunos turistas disfrutan de su mentalidad de espíritu libre, Bianca Duran, estudiante de mercadotecnia de tercer año, está en contra de cruzar la frontera.

“Cuando estaba en preparatoria, tenía una amiga que la mataron por la violencia y desde entonces, no he regresado a Juárez”, Bianca dice. “Mi padre también ha perdido algunos amigos cercanos. Me invitan, pero soy estoy firme con mi decisión de no ir”. Alfredo Torres, gerente de Kentucky Club, dice tener más gente que visitan al bar. Recuerda que durante la guerra contra el narcotráfico habría 30 personas en una noche normal, hoy asegura ahora son entre 50 a 200.

Chelsea Knapp, maestra de mercadotecnia de la preparatoria Franklin, solía cruzar por diversión a Juárez cuando tenía 15 años de edad. Gracias a un incidente con la policía mexicana, Esther, la madre mexicana de Knapp, quien fuera una de las guardias de Reno, (un bar que salio del negocio) supo de sus aventuras en Juárez. Ahora, Knapp está convencida de que los adultos jóvenes no deben cruzar, no por la ciudad, sino por los efectos del alcohol en menores de edad que propicia a decisiones impropias.