Between you and me, bad things are bound to happen, and all we can really say is, “Sorry baby….”

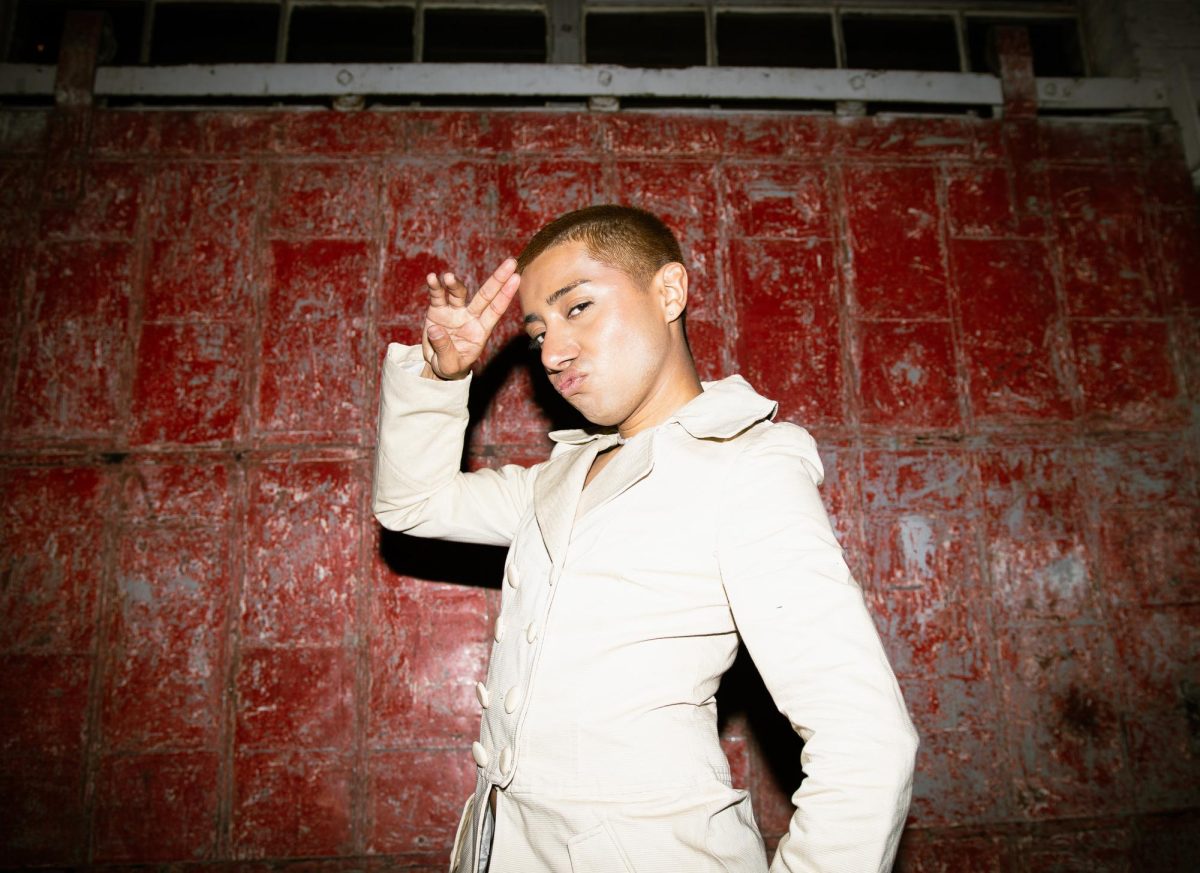

This is the debrief Rumi and I pieced together of A24’s dramedy Sorry Baby, directed, written, and starred by Eva Victor. Deserving of all its flowers, this film is a quiet powerhouse that will leave audience members tangled in deep thought long after the credits roll. As 20 something year olds watching, we were completely taken by the two strong leads: Best friends, later discovered on the big screen. So, what’re our thoughts? Thank goodness you asked:

Rumi’s Take:

Often, society looks at a person who’s lived through a tragedy and defines them as nothing more than that experience. It becomes them. Who they once were is nothing more than a headless apparition. This is the exact outdated narrative that Eva Victor resisted for their main character of the film, Agnes, who went through something as she herself puts it, “really bad.”

A once self-assured young college student, a standout in her graduate English class and an extraordinarily gifted writer, becomes very unsure of every move she makes after that day. People who once envied her, now look at her with pity, and everyone she tries to share her experience with, acts scared and uncertain of how to continue a conversation which many would consider too heavy to talk about in the first place.

With the exception of Liddy.

The only person in Agnes’s life who never judges her. While their friendship is shown through different phases of their life, from the time they shared the same room during grad school, to then living across different states. Liddy remains a constant for Agnes, and so does Agnes for Liddy. Even when romantic interests enter the film, at best they come in second to the truest love of them all: the love between two best friends.

The film’s strength—in my opinion— lies most heavily in its skillful avoidance of the dreaded over explanation.

Which riddles many dialogues in modern film narratives. While in some cases it works to a movie’s advantage, in most cases, it acts as a crutch; becoming the very thing standing in the way of making a film feel more real. Anyone can tell you that in their own lives, words never matter as much as how we deliver them, and it is through these undertones that we learn more about the people we interact with. And it seems that Sorry Baby understands this very well, using subtle drops of a smile, or a prolonged stare, or the inflections of a character’s voice when they speak, to deepen the film’s emotional depth.

We see this most deliberately on the day of Agnes’s “very bad thing.”

Agnes’s experience is never explicitly shown, and in the minutes after, we see a hollowed-out version of her driving away. Entirely frozen. She enters her house to a studious Liddy, and says, “my pants are broken.” The scene then cuts to her in the bathtub with a concerned Liddy seated beside her as Agnes walks her through what has just unfolded. A pause of silence fills the room, until we hear Liddy respond, “Yes babe, well. That sounds like… that sounds like that.” What happened to Agnes is not named for what it was—that would be far too easy. But through carefully chosen and simple words shared between both women, and the way in which they deliver their lines, we as viewers are immediately pulled into their pain.

Through Agnes’s character, the familiar victim/survivor narrative often sold by storytellers is immediately disrupted. There’s a widespread tendency to reduce characters to their traumas, overlooking the harm in valuing them only through the lens of their suffering. However, the film resists this outdated trope, using a series of thoughtful dialogues to assert Agnes’s humanity beyond her pain.

Now Dom’s Take:

I haven’t seen such an intentional and emotional intelligent film as strong as Sorry, Baby.

Riddled with its charming dark humor and deadpan acting, Victor takes a topic so bitter and vulnerable and turns it into art, explaining how trauma interrupts time and change through the lens of stillness and silence. These narrative voices are potent, and they take back their power from the hands of trauma and life after, at least for Agnes. From their accentuation of non-verbal and verbal dialogue to their scenes chosen to utilize either/or, one thing becomes clear:

It all strips down to the raw power of choice.

Instinctively almost, it feels like Victor’s perfect choice is in every scene. Behind every shot, there’s a will and reason. Because of that, we see Agnes go through her fair share of “feedback” when she finally chooses to verbalize this “bad thing” to those who hold authority and power to respond (at least) with a proactive conflict resolution.

A line that hasn’t left me is: “We are women. We know how you feel.”

These were the words said to Agnes by two female lawyers she spoke to about her case, before they pivoted from their superficial sympathy to then emphasize , “we can’t do anything to help you.”

We are women. Of course, the generic response. Who spread this false rhetoric that this enables comfort? When realistically, one cannot possibly know, indefinitely, how Agnes must feel. Sorry, Baby shares that same punch line and rage. (Finally, someone is addressing this.)

The film isn’t “slow,” it was just rumbling quietly in my chest cavity.

It’s quiet, contemplative nature requires a patient viewer, someone willing to sit with the weight of one’s trauma and witness time being an unreliable narrator to Agnes’ life.

Victor also normalizes the non-linear process of healing. It’s a choppy timeline with sectioned-off chapters—somehow that’s easier to swallow trauma down that way.

This film also housed a safe haven for the art of surrendering.

How intentional sharing is a choice too. Whenever Agnes verbalizes the “bad thing” it’s grounded in fragments of her circumstantial truth. Surrendering that story to another’s hands takes grit and proves to be a reason many don’t speak up to begin with. Once it’s spoken, belief becomes optional, inferring only through what is left unsaid— the weight between the sentences and pauses. Even if those who we share our grief with weren’t there to witness what happened, they now hold part of it. And the weight once carried solely by two hands, becomes lighter. Till it no longer belongs to us anymore.

So, what stuck to us even after the credits rolled? This:

Sorry, Baby is for the besties that just want to laugh but have a thorough cross-examination afterwards so touching it feels like therapy (as Rumi & I did). It showcases the power of gravity-defying friendship. Who’s that devoted friend that’s stayed through the “bad things?” Who’s that friend that you entrust to share your “bad things” with? Without fear of them becoming suddenly scared, judgmental, or pitiful?

Evidently, we all have that one friend who carries an unspoken golden rule with you that you’ll be their children’s godparent or Tia/ Tio. Which makes it the perfect ending to the film: The arrival of Liddy’s baby, Jane. What lies profoundly in the last scene is a strong monologue to Jane from (aunt) Agnes: a tiny pocket of poetry. A moment exclusively for them. We, the audience, just happened to be the subtle bystanders. There’s much beauty in realizing you could be that very person you wished you had growing up as a kid and as an adult going through “bad things,” to your little sisters, brothers, nieces and nephews.

Overall, this film was beautiful, affirmative and full. Sorry, Baby may not be for everyone, but it’s for the ones that get Agnes and/or Liddy. Or the ones that see themselves in Victor’s writing or humor. Undoubtedly, the film welcomes everyone and wraps them in an unhurried intimate story that makes you wish you could sit in that world forever.